Free primary education (FPE) was introduced in Kenya in 2003 resulting in a dramatic increase in the number of children enrolled in schools. The influx of additional pupils has impacted negatively on the quality of education provided – for example overcrowded classrooms, lack of teachers and inadequate infrastructure but nevertheless many children still do not attend the public schools provided by the Kenyan Ministry of Education.

Perhaps up to a quarter of Kenyan children do not attend public schools because in the first place there are not enough schools, particularly for those who live in crowded slums like those in Nairobi. The Mathari slum in Nairobi for example has only about three public primary schools nearby which can serve two thousand children at most, although there is an estimated more than three hundred thousand children of school age in Mathari.

Secondly many families cannot afford the associated costs with FPE at public schools – uniforms, books, transport etc. Instead, the children of these families often attend what are known as non-formal or informal schools which are initiated by individuals or organizations and which may be supported by communities, religious groups or NGO’s.

Some estimates suggest there may be over 1600 of these schools operating in Kenya, although accurate figures are difficult to obtain. Most operate in temporary or makeshift shelters and charge little or no fees. Most pupils are from poor backgrounds and where schools provide a midday meal it can often be the only food the child eats that day. Whilst the schools endeavour to teach the same national curriculum that is taught in public schools they operate largely with limited resources and without trained teachers. Only a fraction of the schools receive any form of government support.

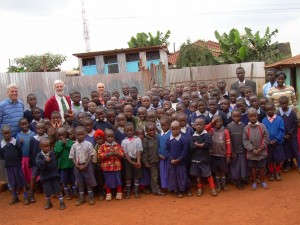

Teachers and pupils at an informal school in Kawangere

On our recent visit to Nairobi, Moy and Brian visited several informal schools in the Kibera and Kawangere slums.

Kibera is the biggest and the poorest African slum with an estimated population of around one million.The Kenyan Government does not recognize Kibera’s existence and as a result there are no title deeds, no provision of sewage, water, roads, government schools, hospitals or services of any kind. Most houses are wooden shacks with a mud floor and a tin roof with no toilets or running water. The schools will usually have mud/dirt floors, grey mud walls and old school wooden pews. The classes may be held in a room the size of an average westerner’s lounge room holding as many as 60 children and with no books, no pens, pencils or other writing materials.

Many of the residents of Kibera have HIV/AIDS.

Following the recent Universal Periodic Review of Human Rights in Kenya, the Kenyan government accepted a recommendation to “Strengthen its educational policy to guarantee the required quality of education, accessible to all members of its population, especially the marginalized and most vulnerable groups” . The Edmund Rice Network Justice and Advocacy group will be working to ensure the Kenyan government fulfils this commitment