Corporal punishment was banned in Kenyan schools in 2001. Despite this, the practice continues to be widespread. Many teachers, parents and caregivers remain unconvinced of the value of alternative methods of disciplining children and the legal system appears unwilling to deal with any teacher who violates the rights of children in this matter.

Belief in the value of beatings and other forms of punishment in the upbringing of children is deeply embedded in Kenyan society and teachers are often pressured by parents to ensure that it occurs. Failure to inflict corporal punishment is often interpreted as demonstrating a lack of concern for the child.

For these reasons the elimination of corporal punishment from schools is a difficult task.

In an effort to address this problem the Edmund Rice Justice and Peace group set out to find ways to engage some teachers and students in exploring alternative approaches to disciplining children in schools.

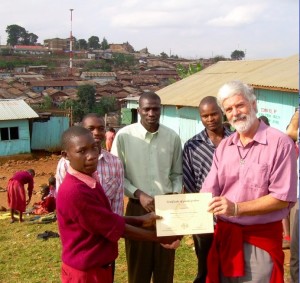

This was done by involving teachers and students from three different informal schools in Nairobi in an essay writing competition. The exercise aimed to explore the teachers and students understanding of corporal punishment – their knowledge of the law, their experiences and feelings about the practice of caning and to gather suggestions about some of the alternative ways that could be used to discipline children in schools that would not reduce their dignity or violate their rights.

The essays revealed that there is a need for further education of teachers, students and parents in the area of children’s rights and that whilst teachers and students were not happy about the use of caning they lacked knowledge about alternatives.

Nevertheless a number of valuable suggestions emerged that included counselling of students, explaining the consequences of behaviour to children, rewarding good behaviour, promoting a wider debate about the issue, using case studies to demonstrate the negative effect of practices such as caning, and encouraging teachers to share their best practice in regard to student discipline.

The Edmund Rice Justice and Peace group is committed to continue to work towards promoting the rights of children and the implementation of positive forms of discipline in Kenyan schools.

Thanks to Johnstone Shisanya, Executive Officer for the Edmund Rice Network in East Africa for supplying the information for this article.

As notorious practitioners of corporal punishment in all their schools both in Ireland and abroad, most notably revealed in the Ryan Report,it is hard to understand why the Christian Brothers, above all, should be concerned about continuing corporal punishment in schools in Africa.

It would be more convincing if they would clarify whether corporal punishment has ceased in all the schools in Africa which they manage and control and in which they are in a position to insist that the law banning the practice is observed.

That corporal punishment was used in Christian Brothers schools in Ireland and abroad is not in any dispute, as has been revealed, accepted and apologized for on many occasions. This very reason alone ought lead one to understand very easily why Christian Brothers are concerned about its continuing practice anywhere in the world, not only in Africa.

Having lived and worked in East Africa since 1993, I can attest to the points made in the article, that there still appears to be deeply entrenched attitudes in many people, families and institutions that corporal punishment and other modes of physical punishment are acceptable and, indeed, needed. It is a difficult and long term process of education to make any changes in these attitudes. In the interest of broadening some readers’ education about the actual situation of Christian Brothers working in Africa, I offer the following thoughts.

Since August 2009, all Christian Brothers ministries in Africa (whether schools or other projects) have come under a common set of policies and protocols for Child Protection. Among many of the rules and guidelines is that corporal punishment is banned, thereby aligning themselves with the Law. In East Africa, with which I am most familiar, every school or project that comes under the management of the Christian Brothers has a Child Protection Coordinator whose responsibility it is to work with the head teacher/manager to implement the Child Protection Policy. There is also an overall East Africa Child Protection Officer whose responsibility it is to support and oversee this implementation. These mechanisms, along with the authority of the Trustees of the schools and projects, enable the Christian Brothers to insist that the Law is followed and that corporal punishment is banned.

However, it does not stop there because “the Law” in itself does not change attitudes. For this to happen, education is needed and an offering of real alternatives. What the writer described in the article (essay writing and engagement) is a small contribution in the long term term investment of transforming minds and hearts to a better way of educating and treating children. Conducting workshops for teachers to introduce them to positive discipline is another.

In all this, it is my experience to note that the Christian Brothers, along with other small groups of educators, are leading the way in East Africa, to ensure that the law is observed, insisted upon and, very importantly, that people are helped to see an alternative way forward.

I am glad to note that having beaten students for so many years in their schools around the world, starting in Ireland and continuing until banned there by civil authority in 1982,the Christian Brothers,as late converts, are doing a volte-face and are now presenting themselves as champions of educational reform.

It is of note that corporal punishment still continues in 2010 in Catholic schools around the world, including Africa, despite the Vatican becoming on 24 April 1990 an early signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child whose Committee has several times expressly disapproved of corporal punishment in schools

Among other aspects of this reprehensible practice, which did so much psychological damage,not least I suspect to the beaters themselves,is the fact that in opposition to the stated views of its founder Edmund Rice and in defiance of the instructions of several Superiors General of the Christian Brothers who expressly directed the practice to cease in their schools, most of their members still continued the practice unabated – and were allowed to continue it -until it became a criminal office to do so.

It does not say much for the acceptance of the vow of obedience by members or the control exercised by superiors who allowed this insubordination to continue.